Republican lawmakers subpoenaed by Jan 6. committee

Fox News correspondent Chad Pergram has the latest on the committee on 'America Reports.'

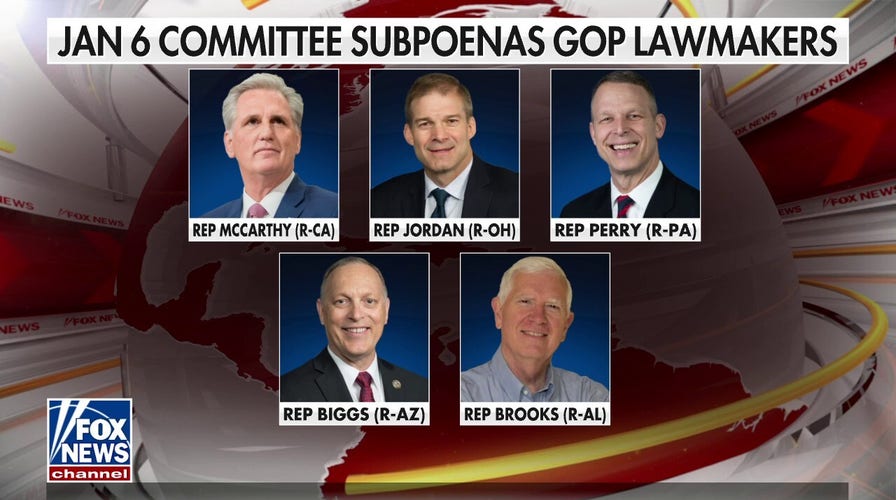

They are the "1/6 Five."

The House committee investigating last year’s riot took the extraordinary step recently of issuing subpoenas to five sitting lawmakers: House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., along with Reps. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, Scott Perry, R-Penn., Andy Biggs, R-Ariz., and Mo Brooks, R-Ala.

The panel investigating has asked these lawmakers to sit for depositions for months. Fox News is told there could be more information forthcoming on additional "material witnesses" who are Members of Congress.

The 1/6 committee is slated to begin a round of public hearings on June 9. Some in prime time. The witness lists are unclear. But what these members knew or were involved with leading up to, on and after January 6 is key.

Fox News is told the committee intends to present damning information about these members in the hearings and in its final report. So, if members don’t comply with the subpoenas, that only adds to the narrative the panel is weaving. In fact, the lack of compliance by the lawmakers could even give the committee the opportunity to generate a "sight-byte" at the hearings. The panel might extend invitations for these members to attend. Then note their absence. The cameras focus on a set of empty chairs at the witness table, each adorned with a nameplate of the AWOL figures. Aides could place a small glass of water next to each name placard, beads of sweat dotting the glass. This could only underscore the intransigence of the witnesses.

HOUSE REPUBLICANS TO MAKE PROTECTING WOMEN'S SPORTS A ‘PRIORITY’ IF THEY RETAKE MAJORITY

The committee could then call other witnesses or present evidence or provide details about the actions of the subpoenaed members. That is the goal of the committee: underscore who knew what about January 6.

Now, on issuing subpoenas:

The decision to issue the subpoenas to sitting lawmakers is a new phenomenon on Capitol Hill. Never before has Congress issued subpoenas for testimony from its own members. That’s partly because lawmakers, as members of the House and Senate, have always engaged in such requests for information - say from the House Ethics Committee or other panels.

Only twice had Congress even issued subpoenas for the documents of lawmakers. In 1993, the Senate voted to subpoena the diaries of late Sen. Bob Packwood, R-Ore., as he faced allegations of sexual harassment. In 2010, the House Ethics Committee subpoenaed the financial records of former Rep. Charlie Rangel, D-N.Y., as part of its inquiry into his conduct.

If members don’t comply, Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution grants the House and Senate the right to mete out discipline for its members, ranging from a fine, a reprimand, censure or expulsion.

And that’s why the House and Senate generally don’t issue subpoenas to their own members. An internal disciplinary process exists to sanction lawmakers. By its nature, issuing a subpoena conceivably takes the process outside of Congress.

If the "1/6 Five" don’t comply with the subpoenas, the House could vote to hold their fellow lawmakers in contempt of Congress. That remedy is usually reserved for non-members. The House has voted to hold former Trump aides Steve Bannon, Dan Scavino, Peter Navarro and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows in contempt. The House then sent the criminal referrals for contempt of Congress to the Justice Department. So far, the Justice Department has only prosecuted Bannon. His trial comes in July.

However, it hard to prosecute a sitting member for contempt of Congress. That’s because Article I, Section 5, empowers Congress to discipline members. It’s possible the executive branch could cite Article I, Section 5 as a reason to ignore a contempt citation from Congress. And even if the DoJ did take up the contempt resolution, a federal judge could immediately toss the prosecution, noting Article I, Section 5.

But that brings us to Article I, Section 6 of the Constitution. That’s where you’ll find what’s called the "Speech or Debate" clause. This provision inoculates lawmakers from prosecution and certain inquiries related to their official duties.

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), Rep. Jim Banks (R-IN) and Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH) attend a news conference on July 21, 2021 in Washington, DC. (Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

Granted, the speech or debate clause doesn’t protect lawmakers from prosecution just because they are sitting lawmakers – especially regarding something as serious as a riot at the Capitol related to the certification of the Electoral College. However, the speech or debate clause prevents the executive branch from maliciously prosecuting a lawmaker as part of an effort to influence how they vote or conduct Congressional business. The speech or debate clause also prevents law enforcements (again, from the executive branch) from seizing the official papers and documents of a lawmaker. In other words, the executive branch just can’t go in and conduct a raid of lawmaker’s office. There is a buffer zone between the executive and legislative branches of government.

This was a problem in the spring of 2006 when the U.S. Capitol Police (serving the legislative branch) allowed the FBI (serving the executive branch) to execute a weekend raid on the Congressional office of former Rep. Bill Jefferson, D-La., in the Rayburn House Office Building. Such a foray raised Constitutional issues – despite the eventual prosecution and conviction of Jefferson on bribery charges.

But, if the "1/6 Five" continue to resist the subpoenas, the House has another, perhaps exceptional option. The House could try to hold the five members in question in what’s called "inherent contempt." This is where the House executes the punishment itself without relying on the executive or judicial branches. The House Sergeant at Arms could potentially "arrest" the members in question and "hold them" unless they agreed to comply.

In 1927, a Senate panel issued a warrant authorizing a Senate law enforcement official to take into custody a witness who refused to comply with a subpoena. A court ruled that the Senate exceeded its authority in this instance.

Congress used this tactic in the 1790s to arrest and actually hold certain newspaper publishers accused of printing seditious content. The House also held a Commerce Department official in inherent contempt in 1934 as it investigated an air mail scandal. Congressional security officials arrested the official but didn’t lock them up in the basement of the Capitol. The official spent ten days locked up in a swanky suite at the Willard Hotel in downtown Washington.

Deploying the inherent contempt option against sitting lawmakers would mark a dramatic escalation of events – exceeding even the committee’s decision to issue subpoenas.

The tactic of issuing subpoenas for sitting members creates a potentially dangerous, new precedent for Congress.

If Republicans win control of the House, they too could begin to issue subpoenas to members - say to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., - about what she knew regarding security at the Capitol on 1/6.

But there is a major downside in this for Republicans, too.

The GOP has made clear it intends to conduct investigations into the Biden Administration and conduct aggressive oversight if they win the House this fall. The topics range from the border to the pandemic to baby formula. Some Republicans have threatened Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, and, even President Biden, with impeachment.

That would inevitably require committees to issue subpoenas.

Granted, a subpoena to an administration official (other than the President) or others not serving in government is not unheard of. Those are much more routine than subpoenas issued to sitting lawmakers. However, the defiance of the five GOP members to comply with a subpoena severely undercuts Republican arguments if they demand that officials appear before Congress – if the GOP is running the show next year in the House.

So what will happen?

"We don’t want to dignify what they’re doing," said Biggs when asked on Fox News if he would comply with the subpoena.

Brooks even indicated recently that if the committee wanted to hear from him, it would have to issue him a subpoena. The panel took up Brooks on that offer. Brooks has declared that he wouldn’t help Pelosi and 1/6 committee member Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wy., "cross the street."

Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon, D-Penn., conceded that the subpoenas are "excessively rare. But then again, so are insurrections." Scanlon said she would "look forward" to holding the members in contempt if they don’t comply with the subpoena.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But we have no idea if the House will ever do it.

Sources close to the committee have confided to Fox News for months that they don’t truly need the testimony of the "1/6 Five." A failure by those lawmakers to comply probably helps those members politically with pro-Trump portions of the GOP base. And frankly, no-shows by those lawmakers helps the committee crochet a storyline that they have something to hide about the Capitol riot.