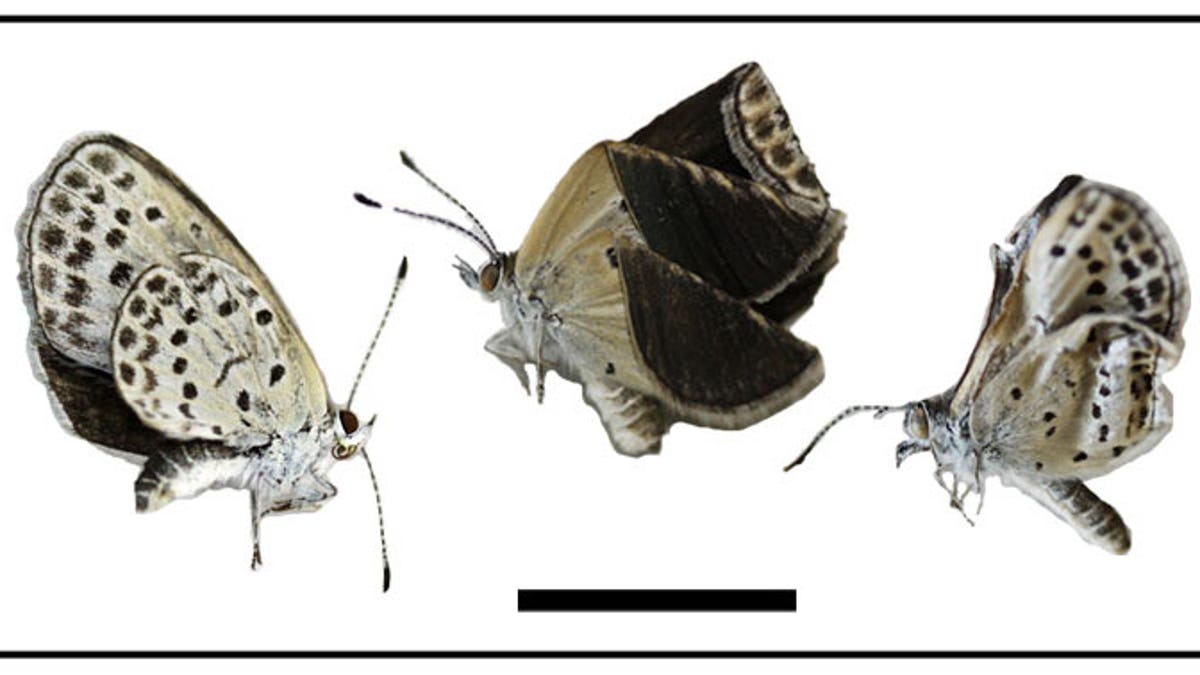

Butterflies near Fukushima, Iwaki, and Takahagi showed wing size and shape deformations. (Hiyama et al, Nature.com Scientific Reports)

One legacy of the Fukushima nuclear disaster last year has already become apparent through a study of butterflies in Japan: Their rate of genetic mutations and deformities has increased with succeeding generations.

"Nature in the Fukushima area has been damaged," said Joji Otaki, a professor at the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa, who is the senior author of the new study.

The abnormalities, which the researchers traced to the radiation released from the nuclear power plant, include infertility,deformed wings, dented eyes, aberrant spot patterns, malformed antennas and legs, and the inability to fight their way out of their cocoons. The butterflies from the sites with the most radiation in the environment have the most physical abnormalities, the researchers found.

"Insects have been considered to be highly resistant to radiation, but this butterfly was not," said Otaki.

The Tohoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, cut off power to the Fukushima Daiichi plant, leading to meltdowns that released radionuclides including iodine-131 and cesium-134/137.The researchers combined laboratory and field studies to show the radionuclides caused the deformities and genetic defects. Butterflies netted six months after the release had more than twice as many abnormalities as insects plucked two months following the release, the team found. The rise in mutations means radiation from the accident is still affecting the butterflies' development, even though levels in the environment have declined, the study concluded. [See Photos of Fukushima's Deformed Butterflies]

"One very important implication of this study is that it demonstrates that harmful mutations can be passed from one generation to the next, and that these might actually accumulate and increase over time, leading to larger effects with each generation," said Timothy Mousseau, a professor of biology at the University of South Carolina who studies the impacts of radiation from Fukushima and from the 1986 Chernobyl explosion in Ukraine.

Mousseau, who was not involved in this study, added, "It is quite concerning to see accumulated effects occurring over relatively short time periods, less than a year, in Fukushima butterflies."

Radiated butterflies

At the time of the disaster in March 2011, pale grass blue butterflies (Zizeeria maha) were overwintering as larvae. Two months later, Otaki and his colleagues collected adult butterflies from 10 locations. They observed changes in the butterflies' eyes, wing shapes and color patterns.

The researchers had been studying the pale grass blue butterfly for more than 10 years. The insects live in the same places as people – gardens and public parks – which make them good environmental indicators, and they are sensitive to environmental changes, said Otaki.

The team also bred the collected butterflies at the university's labs in Okinawa, 1,100 miles (1,750 kilometers) from Fukushima. They noticed more-severe abnormalities in successive generations, such as forked antennas and asymmetrical wings.

Last September the team collected more adults from seven of the 10 sites and found the butterfly population included more than twice as many members with abnormalities as in May: 28.1 percent versus 12.4 percent. The September butterflies were likely fourth- or fifth-generation descendants from the larvae present in May, the authors reported.

Deformities inherited

It is likely that the first generation of butterflies suffered both physical damage from radiation sickness and genetic damage from the massive exposure to radioactive isotopes after the disaster, the researchers reported. This generation passed on their genetic mutations to their offspring, who then acquired their own genetic defects from eating radioactive leaves and from exposure to low levels of radiation remaining in the environment. The cumulative effect caused successive generations to develop more serious physical abnormalities. "Note that every generation was continuously exposed," said Otaki.

Mousseau said, "This study adds to the growing evidence that low-dose radiation can lead to significant increases in mutations and deformities in wild animal populations."

The findings are consistent with previous studies in Japan and at Chernobyl, Mousseau added. "The ecological studies that we have conducted found that the entire butterfly community in Fukushima was depressed in radioactive areas, as were the birds, and that the patterns seen in Fukushima were similar to what has been observed in Chernobyl. If the plants and animals are mutating and dying, this should be cause for significant public concern."

The results were published Aug. 9 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Editor's note: This story was updated at 5:20 p.m. to correct the spelling of Timothy Mousseau's name.

- In Pictures: Japan Earthquake & Tsunami

- Gallery: Dazzling Photos of Dew-Covered Insects

- Butterfly Gallery: Beautiful Wings Take Flight

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.