Grumpy Cat arrives at the 2014 MTV Movie Awards in Los Angeles, California, on April 13, 2014. (REUTERS/Danny Moloshok)

New research suggests exposure to a common parasite carried by cats may make humans more prone to angry outbursts like road rage.

The study, published Wednesday in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, drew a link between toxoplasmosis, and intermittent explosive disorder (IED) and increased aggression. Toxoplasmosis is transmitted through the feces of infected cats, undercooked meat or contaminated water. An estimated 30 percent of all humans carry the parasitic infection.

"Our work suggests that latent infection with the toxoplasma gondii parasite may change brain chemistry in a fashion that increases the risk of aggressive behavior," senior study author Dr. Emil Coccaro, Ellen. C. Manning professor and chair of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, said in a news release.

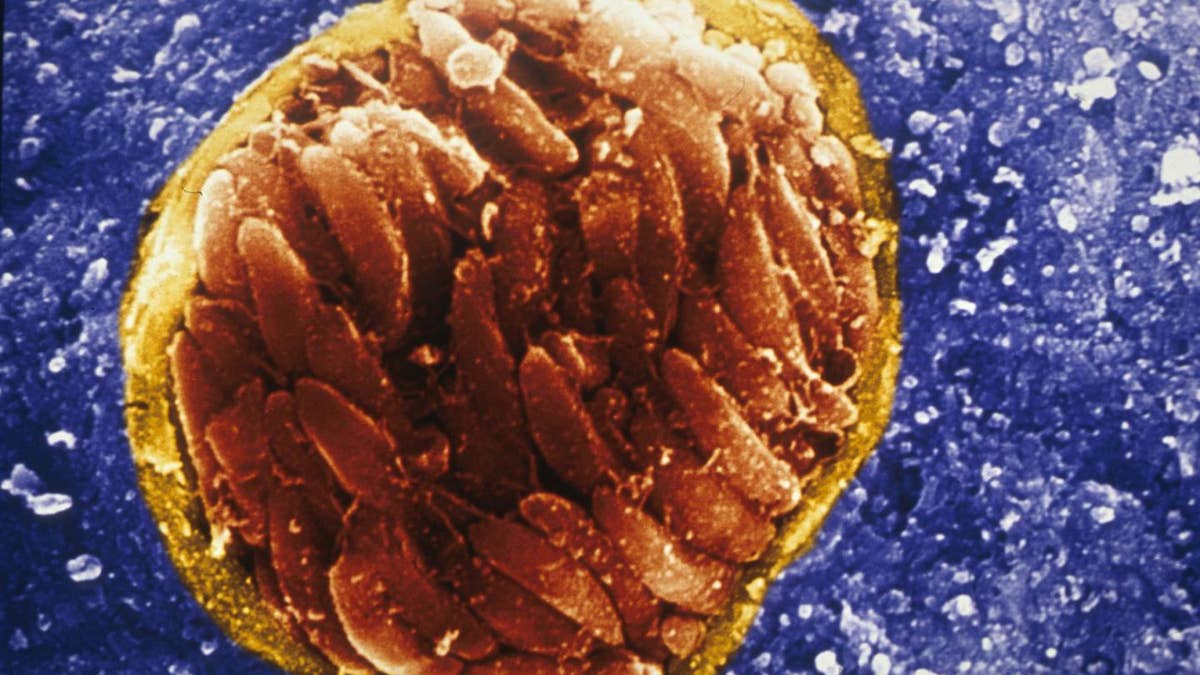

This is a scanning electron micrograph of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, tissue cyst in brain of an infected mouse. (David Ferguson)

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, defines IED as recurrent, impulsive, problematic outbursts of verbal or physical aggression that are disproportionate to the situations that trigger them. According to the release, IED affects an estimated 16 million Americans— more than bipolar disorder and schizophrenia combined.

For the study, researchers studied 358 adults who were evaluated for IED, personality disorder, depression and other psychiatric disorders. Study authors also rated them on traits associated with those conditions, and then divided them into three groups: IED individuals, healthy controls with no psychiatric history, and individuals with some psychiatric disorder history that was not IED.

A blood test revealed the individuals diagnosed with IED were more than twice as likely to test for positive toxoplasmosis exposure (22 percent) compared with the healthy control group (9 percent).

Authors acknowledged a link between exposure to the infection and IED, but they cautioned that further study is needed to determine a causal effect.

"Correlation is not causation, and this is definitely not a sign that people should get rid of their cats," study co-author Dr. Royce Lee, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, said in the release. "We don't yet understand the mechanisms involved— it could be an increased inflammatory response, direct brain modulation by the parasite, or even reverse causation where aggressive individuals tend to have more cats or eat more undercooked meat. Our study signals the need for more research and more evidence in humans."

Coccaro and his team are now doing just that in hopes of better understanding the relationship between toxoplasmosis, and aggressive behavior and IED.

"It will take experimental studies to see if treating a latent toxoplasmosis infection with medication reduces aggressiveness," Coccaro said in the release. "If we can learn more, it could provide rational to treat IED in toxoplasmosis-positive patients by first treating the latent infection."