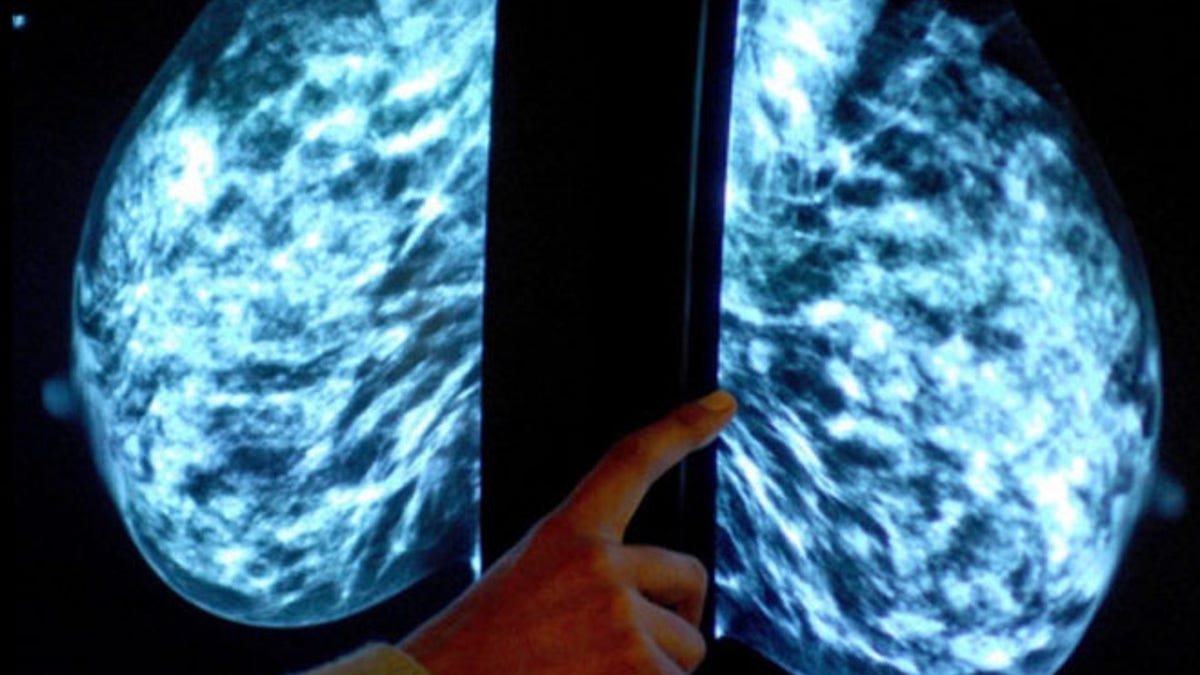

A new report found that the long suspected breast cancer cluster near San Francisco may be more myth than medicine. (Associated Press)

Affluent white women in Northern California have been told for decades that they face an elevated risk of breast cancer, but a new investigation of the reputed cluster – the citing of which has stoked fears as well as fund-raising - shows it could all be a case of junk science.

An extensive report in the Pulitzer Prize-winning weekly newspaper Point Reyes Light highlighted how the Bay Area media contributes to the anxiety of white women in Marin County with headlines like “Unseen Killer Stalks Marin” and “Breast Cancer Amid Affluence: High Rate in Marin County Appears Tied to Wealth, Education,” even though evidence shows the disease is no more prevalent there than in other places.

In the 11-part report, investigative journalist Peter Byrne found that increased diagnosis of the disease is due to the fact that wealthy and educated women in the pristine county, as well as other communities like it, tend to be more proactive about their medical care. While early diagnosis is clearly beneficial, the skewed interpretation has left women in Marin County and other wealthy, white, suburban enclaves, including Long Island, N.Y., Cape Cod, Mass., and areas near Seattle and Los Angeles, believing that the dread disease selectively targets them.

“People who utilize medical services the most are going to be diagnosed with more diseases.”

“Simply put, federal and state data show that women living in mostly white suburbs akin to Marin get substantially more screening mammograms than do women in lower-income communities,” Byrne, whose series is entitled “Busted! Breast Cancer, Money and the Media,” said. “High rates of screening discover more cancers, and also return comparatively high rates of false positives.”

Byrne’s series charges that scientists unable to explain why certain women would be more at risk on the basis of race have nonetheless spent millions of taxpayer dollars speculating about the supposedly carcinogenic lifestyles of wealthy suburbanites, while ignoring the simplest, most logical explanation.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, an internationally renowned expert in cancer risk assessment and the director of the Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics at the University of Chicago, is one of several authoritative sources Byrne cites as rejecting claims affluent, white women are at increased risk of breast cancer.

“People who utilize medical services the most are going to be diagnosed with more diseases,” Olopade said. “Because people with insurance get the most mammograms, a cancer registry’s breast cancer incidence reporting will be skewed toward people with access to good health care services.”

The real risk of the misguided claims, writes Byrne, are that they drive unnecessary fear and improperly influence research priorities. For instance, Marin County’s health department has excluded non-white women from most of its breast cancer studies, and politically driven funding by federal agencies has poured millions of dollars into such whites-only studies, despite the fact that the breast cancer mortality rate for African Americans is 40 percent higher than whites, according to the report.

Following the report, California Assemblyman Marc Levine, D-Marin, asked the state Department of Public Health to investigate the issue, with an eye toward reforming the cancer registry system. The series also has had an effect on the very media Byrne took to task, as Chronicle Science Editor David Perlman wrote in a letter to the Point Reyes Light that it “should compel health officials in every American jurisdiction—from local health departments to the National Cancer Institute—to re-think the way cancer statistics are misused and how they have misled the public.”

Click here to read the complete series, “Busted! Breast Cancer, Money and the Media.”